13 Jan 2016

Interview with Chris Johnstone: "Burnout is a risk where people are passionate about what they do"

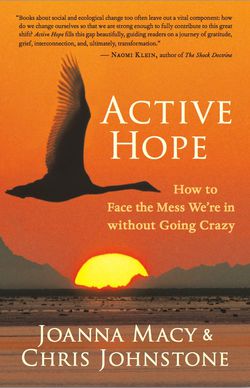

Chris Johnstone is an old friend of this blog, a resilience specialist and writer, author of ‘Active Hope’ and ‘Find your Power’, who is now living in the north-east of Scotland. One is his areas of speciality is balance and burnout, so we felt like the ideal person to catch up with. We started by asking what, for him, is burnout?

“Rather than a definition, I prefer an image. When I think of burnout, I think of the image of a field of wheat that has been over-farmed for years, to the point where soil declines and the field no longer grows very much. We see this happening all around our world where once-fertile areas have decline of topsoil to the point where they no longer produce the same kind of yield. If you think of that in human terms, you can think of somebody who used to be enthusiastic and productive but gets to the point where they feel used up. Where they’re no longer able to offer so much, but importantly their quality of life, their experience of life also really declines. It’s like life goes sour.

Another image I have is of a tube of toothpaste that has been completely used up and every last drop of it has been squeezed out. It’s used up and there’s nothing very much there left.

Burnout isn’t something that you tend to hear about so much in the Women’s Institute or football supporters’ clubs – while it affects many people in stressful work contexts, it does seem to be something activists and change-makers are particularly prone to. Why is that, do you think?

There’s a saying that “in order to burn out, you need to first be on fire”. Burnout is a risk where people have a strong sense of passion behind what they do. If somebody’s very committed to their work, there is research which shows that the people who are most at risk of burnout tend to be those who are most conscientious and sensitive. If you didn’t care about what you were doing, if it wasn’t so important to you, you’d be at less risk of burnout.

There’s a saying that “in order to burn out, you need to first be on fire”. Burnout is a risk where people have a strong sense of passion behind what they do. If somebody’s very committed to their work, there is research which shows that the people who are most at risk of burnout tend to be those who are most conscientious and sensitive. If you didn’t care about what you were doing, if it wasn’t so important to you, you’d be at less risk of burnout.

But also it’s a word that’s going to be talked about more because research is showing very clearly the whole thing about aiming for industrial growth is that people are being squeezed harder and harder in their workplaces. Stress is on the increase, and it’s already one of the major causes of time off work through sickness: stress, anxiety and depression. We live in a more driven society where the casualty rate is going up.

Very often, the organisations who argue that we need a new way of doing things, a new economy and so on, as organisations can often end up being driven and working in much the same way, having the same kind of work culture, as what they’re trying to replace…

There’s an issue here because you look out at the world and there’s so much that needs to be done. We really are in such a dire state in so many ways that you can have that sense of urgency driving us harder and harder. Also for people whose work is basically about service work, there’s often a resource issue. The demand is high but the resources supporting their work are often inadequate. So that puts people under a great deal of strain.

One of the questions that Sophy Banks raised in the editorial piece that she wrote for this theme was “what might it look like if the culture of Transition as a movement, if the DNA that people who, wherever they are in the world pick up Transition and start to work with it meant that there was no burnout” What would that look like, do you think?

First of all, I love Sophy Bank’s piece and point people towards that. It’s a very important piece of work that you and her have done in just opening up the conversation around this area. I think you’d recognise an organisation that had really dealt with burnout if as well as working for change out there in the world, one of the areas of its attention was also what I call “the middle bit of change”. The middle bit of change is the first bit of change is becoming aware of the problem, the third bit of change is having the action response to that. The middle bit of change is everything that happens between awareness and action.

It includes things like our levels of enthusiasm; our levels of energy; whether we even want to look at an issue; if we pay attention to that middle bit of change and we see that that’s part of the work of activism, that would be the kind of thing you’d see in an organisation or a movement that had really come to deal with burnout, where there wasn’t any burnout. If we really paid attention to that, we’d pay attention to things like enthusiasm.

I see enthusiasm as being like topsoil. If you have high levels of enthusiasm, out of that the best yields tend to grow. So if an organisation paid attention to enthusiasm, then they’d look at things like – do people feel enthusiastic about coming to our meetings. Some meetings are boring, they’re heart-sink areas. But if we really paid attention to – what would make this a meeting that people would want to come along to.

I think there are some great examples out there. I’ve given some talks and run some workshops for Sustainable Frome and I was very impressed with them. They had a problem where they had meetings that weren’t that well attended. One of the things they did was they said “let’s meet for a shared meal before we have the meeting, if we’re going to have a film or something, let’s meet first, we all bring along some food and we share it”.

It changed the quality of their meeting from something that people think “oh, I should go” to something that people wanted to go to, that they looked forward to. That’s one of the things, if we can make our meetings things that people look forward to coming to, that will be the kind of thing that will go a long way to making burnout less likely.

I remember Peter Macfadyen in Frome who was one of the people in the group who became the Mayor. He said that when he became the Mayor he would always bake cookies to take along to the meeting and how it changed the quality of the meeting: starting out with some biscuits he’d made before the meeting.

I love that phrase you just used “changed the quality of the meeting.” There’s content in terms of what do we do, but there’s also process which is how do we do it. How do we change the quality of our meetings? It’s seeing that how we do things is as important as what we do; that we live in an economy that’s very focused on product, very focused on what comes out the end of an assembly line. That can also be true of activists. We can judge what we do by the end result. Also we say – how can we do it? Can we do it in a way that is nourishing? Can we do it in a way that is attractive? When we start asking those questions, when we really look at the quality of our meetings, it really changes things.

Sophy’s blog included the quote “burnout is the dirty secret of the environmental movement.” After COP21 in Paris there will no doubt be a lot of burnout, given the expectations and the intensity of those 2 weeks. What advice would you have for the wider climate movement post COP21 with regards to burnout?

One of the first things to say is a lot of this work for our world is hard and there are big disappointments along the way. I draw inspiration from historic examples and particularly the campaign for the abolition of the slave trade. People might know that it was just a dozen or so people who met in an old print shop in London one evening. Out of that, many other things that followed, a movement grew.

What’s less known is that there were huge dips and disappointments in that campaign. There was a period where there were much harsher laws where the campaign closed its office for about seven years. They stopped their meetings and it looked like all was lost. And yet turnings can happen. This is where – one of the things for me is I draw inspiration from adventure stories.

What’s less known is that there were huge dips and disappointments in that campaign. There was a period where there were much harsher laws where the campaign closed its office for about seven years. They stopped their meetings and it looked like all was lost. And yet turnings can happen. This is where – one of the things for me is I draw inspiration from adventure stories.

Adventure stories often have what I call their ‘Chapter 7’ moments. Usually by the middle of a book, certainly by chapter 7, things have gone hopelessly wrong and it all seems lost. But also the story is about turning and change and it’s looking at how we make that more likely.

One of the strengths or qualities that will make a turning or change more likely is resilience. This is why I have learnt so much from you, Rob. You’ve built a whole movement around taking resilience seriously. Part of resilience is community resilience and societal resilience, but also part of resilience is personal resilience. I’ve made this a big piece of my life’s work, looking at what helps us keep going.

I call it finding the ‘up slope’ of a dip. When we get down, how do we climb back out again? We need to see this as centre stage for activism. It’s not some fringe meeting that might happen now and again for people who are touchy-feely types. We need to bring this centre stage.

It is also centrally about an ethic of sustainability. An ethic of sustainability is about looking through a larger lens in time, inhabiting a larger, wider timescape. If a timescape is a period of time that we give our attention to, often it can be quite a narrow space. It can be the period of now plus or minus a few years. If we see this working for our world stuff as something that we need to do for all our lives, it’s a marathon not a sprint, or if it is a sprint it needs to be what they call interval training where you push hard and then you pause and renew.

You push hard and then you pause and renew. If we’re seeing that we’ve got a long distance to go, we need to look at how we find a sustainable pace and how we nourish ourselves to keep going.