5 Oct 2011

Transition: localisation as economic development? An article for the National Trust

Here is an article I wrote that just appeared in the National Trust’s latest ‘Views’ magazine. You can read it below, or download it as a pdf here, or see the whole magazine here.

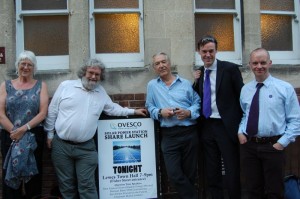

As I write this in May 2011, some amazing things are happening. A report1 from Australia shows that car ownership there has peaked, having been in steady decline since 2004. John Lewis report that, over the last year, trade at their UK out-of-town stores has fallen by 12 per cent while it has remained steady in their stores in town centres, the drop being partly blamed on the rising costs of fuel. A survey2 by B&Q showed that 37 per cent of adults plan to grow some of their own food this summer. In the Sussex town of Lewes, the community energy company OVESCO (Ouse Valley Energy Services Company) has raised over £300,000 to put 540 photovoltaic panels on the roof of the local brewery, Harveys. The brewery brewed a commemorative beer called ‘Sunshine Ale’ to commemorate the event. While there is gloom and doom-a-plenty for those who choose to go in search of it, communities across the UK are just rolling up their sleeves and getting on with building the kind of future they want to see. Clearly they are seeing a gleam of opportunity here.

As I write this in May 2011, some amazing things are happening. A report1 from Australia shows that car ownership there has peaked, having been in steady decline since 2004. John Lewis report that, over the last year, trade at their UK out-of-town stores has fallen by 12 per cent while it has remained steady in their stores in town centres, the drop being partly blamed on the rising costs of fuel. A survey2 by B&Q showed that 37 per cent of adults plan to grow some of their own food this summer. In the Sussex town of Lewes, the community energy company OVESCO (Ouse Valley Energy Services Company) has raised over £300,000 to put 540 photovoltaic panels on the roof of the local brewery, Harveys. The brewery brewed a commemorative beer called ‘Sunshine Ale’ to commemorate the event. While there is gloom and doom-a-plenty for those who choose to go in search of it, communities across the UK are just rolling up their sleeves and getting on with building the kind of future they want to see. Clearly they are seeing a gleam of opportunity here.

One of the most infectious and rapidly spreading approaches is the Transition movement. It began in Totnes in Devon in 2005 and has now spread to many hundreds of initiatives in 30 countries around the world. The premise is a simple one. We are now moving into an increasingly uncertain future, whether because of the debt mountain we sit on, the impending peak in world oil production or the impacts of climate change that we are already seeing around us. The Transition movement argues that our communities have become alarmingly unresilient; that is, they have lost the ability to respond to shock from the outside at exactly the time when we need them to be more resilient.

In effect, the Transition movement, in communities as diverse as Totnes, Tooting, South Liverpool and Tynedale, has been running an experiment for the past four years. The experiment gives people a simple purpose and a set of tools, and invites them to see if they work in that community. It stresses that no one knows how to do this and that the only way we will be able to figure it out is by having a go. It invites creativity, inventiveness and entrepreneurship. Every initiative will look very different, a place-specific assembling of ingredients to create something that is recognisably Transition but which is also distinct to the place. As Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall put it recently, Transition is ‘rather like giving a great cake recipe to a dozen different cooks and watching how their particular ingredients, techniques and creative ideas produce subtly different results’.

Keeping it local

Here are a few stories from what we see starting to emerge in UK Transition initiatives:

Topsham Ales: Transition Topsham (in Devon) decided that the one thing that united their community wasn’t peak oil or climate change, but good beer, and so set out to create a community-owned brewery. They worked out they needed £35,000 to get started, and within five weeks had raised the sum from 56 members who bought shares for a minimum of £500 each. They are now brewing, using local hops, the waste yeast going to a baker and the waste hops to local pigs.

The Malvern Gasketeers: Malvern is home to 109 listed Victorian gas lamps, which were the inspiration for C.S. Lewis when he wrote about the lamp Lucy first discovers in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. Unfortunately, keeping each lamp in working condition was costing the local council £580 per year (£130 for gas, £450 for maintenance). Enter the Transition Malvern Hills ‘Gasketeers’, local energy enthusiasts who have now reduced that to just £70 per year (£20 for gas and £50 for maintenance). They were also able to make the lights ten times brighter than they were before but with no light pollution at all. They are now planning to run the lamps on locally produced methane, which would create local jobs and offer many other spin-off benefits.

Slaithwaite Green Valley Grocery: When their local grocer’s shop announced its closure, a group of people, mostly from Marsden and Slaithwaite Transition Towns (MASTT) suggested a community take-over, an idea strongly supported at a community meeting. Three weeks later they held another meeting and said it would only happen if they were able to raise £15,000 in shares from the community. And three weeks later, they had. The shop is now open and thriving, and has catalysed a growing co-op called ‘Edibles’ set up to supply the shop with local food.

Collective design

What we are starting to see emerging in Transition is an approach founded on the idea of localisation, which is distinctly different from the idea of ‘localism’ being promoted by the present government. Localism is about the transfer of political power to the local level, whereas localisation is about the shifting of economic focus to meet local needs locally where possible, plugging the leaks in the ‘leaky buckets’ that twenty-first-century local economies have become. As such, Transition promotes the idea of localisation as economic development, arguing that if we are serious about our local economic regeneration, we need to seek to create a culture of entrepreneurship and creativity, one in which communities become their own energy companies, their own farms and market gardens, their own developers.

Key is the idea of this not being a process that will come about by accident; it is, at heart, a collective design project. A fascinating example of this comes from Norwich where the local Transition initiative undertook a detailed study called ‘Can Norwich Feed Itself?’, which mapped the local area and its potential productive land in order to answer that question. Their conclusion was that they could, assuming a simpler more seasonal diet. The report identified a number of projects that would be essential for making this happen. These included a new grain mill in the city, two community-supported agriculture projects and an initiative to get local farmers growing oats and beans for local markets. Tully Wakeman, who co-ordinated the initiative, told me:

‘It is important to have a sense of the whole food picture for a settlement such as Norwich. A trap a lot of non-government organisations (NGOs) fall into is overthinking about vegetables. The tendency for people to equate renewable energy just with electricity rather than the range of different ways we use energy is even truer when we look at food. Only one-tenth of what we consume, in calorific terms, comes from fruit and vegetables, yet that is often the main focus for community NGOs looking at food security. Yet where is the other 90 per cent going to come from? Growing vegetables in gardens, allotments, community gardens and so on offers a degree of food security and can happen relatively rapidly. However, the other 90 per cent requires the rebuilding of the infrastructure required for growing, processing, cleaning, storing, milling and distributing grains and cereals, and that takes longer and requires more planning.’

Around the world, communities are actively exploring this notion of localisation as economic development. Mervyn King, Governor of the Bank of England, recently stated: ‘[this] is not like an ordinary recession where you lose output and get it back quickly. You may not get it back for many years, if ever, and that is a big long-run loss of living standards for all people in this country.’ Might it be that engaging with this as an opportunity rather than as a disaster, seeing the strengthening of local economies as a historic opportunity to rethink our economy from the ground up, might be a better approach? The experience of Transition initiatives in the five years since the idea was first mooted would seem to suggest so.

References

1 Millard-Ball, Adam, and Schipper, Lee, ‘Are We Reaching Peak Travel? Trends in Passenger Transport in Eight Industrialized Countries’, Transport Reviews: A Transnational Transdisciplinary Journal, Vol. 31, Issue 3, first published 2011, pages 357–378

2 Research carried out by OnePoll for B&Q; date of press release: 11 April 2011

You can read more about these stories, and many more, in the author’s new book, ‘The Transition Companion’, which you can pre-order here.