Monthly archive for February 2016

Showing results 1 - 5 of 9 for the month of February, 2016.

29 Feb 2016

In her framing editorial for our theme of burnout and balance, Sophy Banks asked:

“What should leaders in our groups and our movement be modelling to show that well being and balance are more important than always doing? To model that it’s not acceptable to override one’s health to give a bit more, again and again? To give value to downtime, social time, listening, stillness, caring in our relationships, honouring and celebrating what really matters in our lives”.

So, in the same spirit that George Monbiot publishes his ‘Registry of Interests’ showing who pays him to do what, I am going to attempt an honest evaluation, rising to Sophy’s challenge, of how, as one of the ‘leaders’ of this movement, I manage balance and burnout in my own life. Feels like a useful thing to do as our burn out theme draws to a close. It is hopefully something I will do on a regular basis, and something, whatever your role in Transition, that I invite you to have a go at too. Ideally you would do this in pairs with someone else, as it’d be useful to get their insights and feedback, but I’ve just given this a stab on my own.

Drawing on on Sophy Bank’s model of what needs balancing, Claire Milne (new Inner Transition co-ordinator) and I have formulated 8 measures, 8 areas where we are trying to achieve balance. I did try to do a score for each one, but found it really difficult to score these in a way that made sense. So how am I ‘doing’?

1. Doing: Being

[By ‘Doing’ we refer to work, fast-paced, mission-related activity, and by ‘Being’ to slowing down, resting, meditating and other nourishing practices, reflecting].

I am probably not very good at this, certainly not as good as I used to be. Having a family, when I am not ‘doing’ Transition, I am ‘doing’ being a Dad and playing my part in running a household. Generally time when I would be meditating, I am too tired to keep my eyes open.

For me, my ‘being’ time takes the form of walks on Dartmoor (about once a fortnight, see right), riding my bicycle (most days, but just into town and back), working in my garden, listening to football on the radio (oddly meditative), listening to new music (might I recommend Max Richter’s recent piece ‘Sleep’ as some extremely fine ‘Being’ music), time just hanging out with family, the rare occasions I get to do any sketching, or rare trips away with Emma (my wife). I do also try to go swimming most lunchtimes, not something I always manage, but it is my conscious effort to try to keep in some kind of shape and to make the space for that.

For me, my ‘being’ time takes the form of walks on Dartmoor (about once a fortnight, see right), riding my bicycle (most days, but just into town and back), working in my garden, listening to football on the radio (oddly meditative), listening to new music (might I recommend Max Richter’s recent piece ‘Sleep’ as some extremely fine ‘Being’ music), time just hanging out with family, the rare occasions I get to do any sketching, or rare trips away with Emma (my wife). I do also try to go swimming most lunchtimes, not something I always manage, but it is my conscious effort to try to keep in some kind of shape and to make the space for that.

However, I do think I am quite good at ringfencing my family time: I try to be home no later than 5.30 every work day, and try very hard to not work on weekends. I also try to model this for the organisation by deliberately taking all of August off work, and switching everything off. I think that would put my score up a little had I figured out a way to score these…

But striving for balance between being and doing isn’t just something that happens at home. In the context of my work, I am fortunate enough to work in an organisation that values being, that has bi-monthly ‘Being’ meetings, and in which speaking about feelings of overwhelm and stretch is welcomed. At times when I have felt overwhelmed, I have also felt overwhelming support. When I visit Transition groups to speak, I always speak up for finding a balance, as a group and as individuals, between doing and being.

One of our Being/Doing activities at work that I rather enjoy is having a Caption Competition in the office loo … a suitably daft photo of one of us that invites peoples’s comments. For me, it adds a quality of playfulness to our working culture that is really precious.

2. Thinking: Feeling

[By ‘Thinking’ we mean generating meaning and knowing through mind, body and rational, logical thought and by ‘Feeling’, generating meaning and knowing through intuition, embodied (in our body) feelings and dreams]

I think it is fair to say that I am more rooted in ‘thinking’, and I do hold to the sense that ideas and thoughts need to be rooted in evidence and research, leaning me more towards ‘Thinking’. However, I do feel like I put a lot of feeling into my writing, speaking honestly and personally, and reflecting a lot on how things impact me personally, something that is also a key element of when I give talks. I have even been known to write blogs about dreams I had.

3. Giving: Receiving

[By ‘Giving’, we mean giving our time, energy, money, commitment, attention, and by ‘Receiving’, we mean accepting appreciation, connection, warmth, money, (self) care].

I’m probably not that great at this, if I’m honest. I am definitely better at giving than receiving. I tend to deflect appreciation onto other people, out of concern at appearing big-headed or ego-driven. I am good at accepting warmth from people, at least that’s the feedback I get, but the fact that I have, after 10 years of doing Transition, not really managed to save any money during that time suggests that perhaps accepting money is something I have some kind of a block around (!). I do think I am good at giving time, energy and attention, albeit in the context of the boundaries around family life as described in 1. above.

4. Talking: Listening

[By ‘Talking’ we mean taking space, sharing our ideas, opinions and feelings, and by ‘Listening’, we mean leaving space to listen to other people’s ideas, opinions and feelings]

I would like to think I am a good listener, and am very open to hearing and working with other people’s ideas and thoughts. That is a culture that runs through Transition Network and how we work, and through most of the other projects I am involved in. It is also something I try to bring to projects I am part of outside of Transition. I would like to think that I am alert and attentive to other peoples’ feelings about things, although I’m not always perfect at it.

Feedback I get from places I go to visit is quite often that they felt I listened well and that they felt heard. When needed, I can take space, share my ideas, but I do try, within that, to be attentive to where those listening are at and how they are receiving what I’m saying.

5. Positivity and strength: Vulnerability

[By ‘Positivity and strength’ we mean feeling solid and optimistic, and by ‘Vulnerability’ we mean allowing ourselves/re-learning how to feel a sense of ‘not knowing’, despair, helplessness and fear].

Sometimes people imagine that, given the nature of what I do, I am somehow relentlessly upbeat and positive, but that’s not the case. Like anyone reading about what’s happening in the world (and receiving Peter Lipman’s ‘Email List of Doom’), I have down days, and moments of overwhelm. But they are surprisingly few and far between. No idea why. Just as my brother-in-law is capable of drinking amounts of beer that would put me under that table several times over without even appearing intoxicated, I seem to be able to digest that stuff and transmute it into doing things.

But life generally can be very overwhelming sometimes. There have been times, which I have written about elsewhere, when coming under attack can be very stressful and exhausting. Or when family pressures and demands, combined with work life, and an overcommitment to too many things, can leave me feeling stretch taught like the skin on a drum. Or when I feel like the work I’m doing isn’t sufficiently challenging or stretching, or like I’m just treading water. At such moments, I have good people to talk to, and TTT’s Mentoring Project, both of which have proved extremely helpful.

So for me, despair isn’t somewhere I go very often.. that could either be because I am somehow in denial, or because I am unusually able to transmute it into something else, I can’t be quite sure, so if I had figured out a way to score this, it would either be a high mark, or quite a low one…

6. Time alone: time with others

[By ‘Time alone’ we mean time spent digesting, resting, nourishing, self care and expressing our boundaries, and by ‘Time with others’ we mean relating and engaging].

I don’t get much time alone, in fact virtually none. What free time I have when I’m not working or away meeting Transition groups I spend with my kids or with Emma. My time alone is time walking the dog, riding my bicycle or swimming. I accept that while I still have kids at home that’s just how it is, they need me more than I need me. I notice that sometime when I am away, such as when I was in Paris for COP21, I give myself entirely to ‘Time with Others’, which over a period of time can be deeply exhausting, so ensuring that ‘Time alone’ is valued and designed into itineraries for trips is a key strategy moving forward. Not a great deal of balance in my life around this one.

7. Screen time/indoors; creativity/in nature

I’m not very good at this one either. I tend to check my phone first thing when I wake up, just to check that while I was asleep nothing utterly disastrous happened in the world (not that there’s much I could about it anyway between then and breakfast…). A screen is often the last thing I see before I fall asleep, and is usually a key part of the time in between too.

I do try though to keep to a strict rule of not working at home once I’m home, and to put my computer away during the weekends, because that time belongs to my family. During August, I aim to take the whole month off, and generally manage to put both my laptop and my mobile away for the full 4 weeks. It is wonderful. I do seek regular time in nature. I would score myself higher on this, but I am aware that my smartphone catches my attention more than it really should, and I need to get better at ignoring it.

8. Self-directed action/ Collaboration

[By ‘Self-directed action’ we mean individualistic expression, protected from group and power dynamics, hero culture, power over etc, and by ‘Collaboration’ we mean working with others collaboratively, observing and engaging with group dynamics].

This is a tricky balance for me. I am, by nature, a self-starter, a do-er, someone who likes to just go for things under my own steam. I am also an artist, and for me, my work is very similar to an arts practice, my blog is my sketchbook and so on, so I have that driven need to create. I think that I used to have more of a bull-in-a-china-shop approach of just getting on with stuff which impacted on those around me.

But my 10 years of being part of Transition Network, with the remarkable team of people I work, and have worked with, has taken me on a real journey into collaboration, and learning many of the skills needed to make it work. I think, in spite of my profile, that I am quite good at undermining any “hero culture” that arises around me, or perhaps just quite good at ignoring it. I would like to think that I am a good team player.

****

Of course, people who know me may entirely disagree with what I have written above, and feel I am deeply deluded and in huge denial. That may be so, and doing this in discussion with others would have helped. My relationship to burnout has been, until recently, a fairly regular one. Once every three -four years I tend to get some kind of bug that flattens me for about 3 weeks. Hasn’t happened for a while though, so perhaps I’m developing a new pattern? Let’s hope so. Perhaps some of the changes I’ve made, outlined above, have contributed to that. What would your Burnout Audit look like?

Read more»

26 Feb 2016

The word ‘fulfilment’ has two distinct meanings. The first, according to the Cambridge Dictionary, is “the fact of doing something that is necessary or something that someone has wanted or promised to do”, and the second “a feeling of pleasure because you are getting what you want from life”. I like the idea of the second one, a life of fulfilment, it’s something we all aspire to, right? You might even argue that we long for fulfilment: at the very least it’s certainly what one might call a Good Thing.

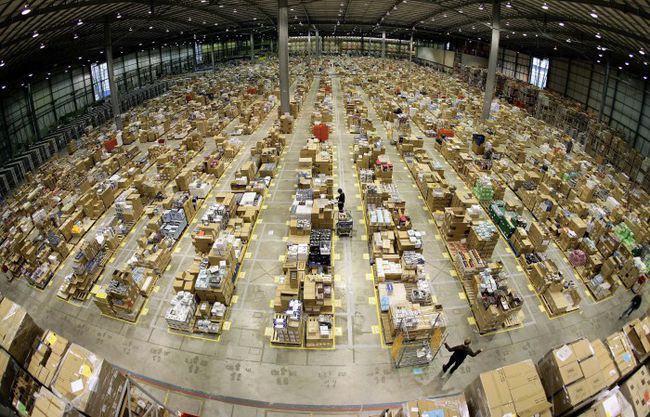

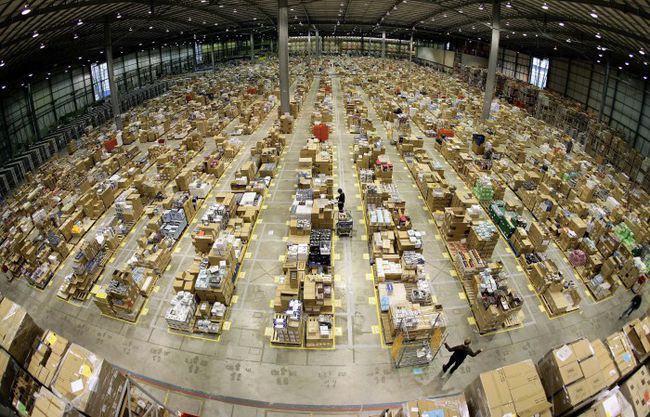

Yet sadly, for many, the term ‘Fulfilment Centre’ doesn’t refer to somewhere with great cake where pleasure and “getting what we want from life” are available on demand, but rather to vast, disorientating, highly stressful working environments designed not to benefit local people or the local economy, but rather distant investors and shareholders, offering the allure of cheap stuff, much of which will end up in landfill within a few months.

The Guardian reported last week that there is great concern in the villages of Sevington and Mersham in Kent that a huge new development being planned on their doorstep is in fact going to be a vast Amazon ‘Fulfilment Centre’ (although Amazon deny this). The new development, which necessitates a new junction onto the M20, will receive £50 million in government funding, including £20 million from the Local Enterprise Partnership (LEP) (more of them in later posts). There is much uproar locally, with one councillor describing Amazon as practicing “the worst kind of corporate citizenship”. I would like to also accuse them of abuse of our fine language.

As regular readers here will be aware, when left to determine their own futures, local town economies, neighbourhood economies in urban areas, can be ‘fulfilment centres’ in the good meaning of the word, meeting their needs in the round, while doing so with virtually no public funding, and paying their taxes. For example, here in Totnes, a rare High Street where 80% of businesses are still independent businesses, I see a lot of fulfilment. I also see it in many other places, in vibrant, diverse, delicious, entrepreneurial high streets, in craft breweries, bakeries, food markets and much much more. As Julian Dobson wrote in ‘How to Save High Streets’:

“The best future for our town centres is not merely as places to buy, but as places to be; places where we can live and act as citizens rather than as consumers. Then they can be places where we rediscover local identity and community, where we can be more fully alive and more fully ourselves. As many a shopkeeper has said, why settle for less?”.

This reclaimed interpretation of the term ‘fulfilment centre’ offers a model of business with a deep sense of finding the right size, of working for a greater purpose, intimately connected to the idea of being a force for the reimagining and rebuilding of the local economy, for nurturing fulfilment, the exact opposite of what the taxpayer is subsidising to an eyewatering degree in Kent. If we get it right, we can create a model that also benefits public health, brings assets into community ownership, builds local resilience. Sounds pretty fulfilling to me.

In our Kentish ‘fulfilment centre’, the government would be gifting £50m of tax payers’ money to a company who raked in £5.3bn sales from online British shoppers last year, yet recorded a profit of just £34.4m and paid just £11.9m in tax. It is a model where that company then goes on to create poorly-paid jobs which make workers mentally and physically ill, and puts out of business the very small and medium sized enterprises that actually give that local economy its resilience and, yes, its fulfilment.

Alongside ‘fulfilment’, there are two other words that I think we need to wrestle back from the Amazons of this world:

- ‘Shift’ need not be a 14 hour, soul-destroying session in an artificially-lit warehouse order picking Jeffrey Archer novels and iPods, shift can also refer to “transfer from one position to another”, to see the world around us shifting, changing for the better.

- ‘Agency’: while agency can refer to the private company through whom people find the kind of work offered in our Amazon ‘fulfilment centre’, it can also refer to refer to “the subjective awareness that one is initiating, executing and controlling one’s own volition in the world”, in other words, that we can influence and affect the world around us.

What we try to do in the Transition movement, and in a huge array of emergent new economy movements and enterprises, is to support people to reconnect to their longing, to support them to shift, and to find their agency, and, as a result, as sense of fulfilment. Would £50m of public money poured into Amazon enable any of those things to happen? No. Quite the opposite.

We need to reclaim our local economies, and to challenge, as the wonderful Fair Tax Town movement is doing, a tax system that undermines resilient local economies and rewards predatory extractive industries like Amazon. But we also need to reclaim our language.

Read more»

19 Feb 2016

I watched the recent BBC documentary on Kids Company, Camila’s Kids Company: the inside story, with great sadness. It told the story of Camila Batmanghelidjh and the unravelling of one of the UK’s best known charities, who did remarkable work helping some of the most disadvantaged kids in the UK. While what happened is clearly complex, and while its demise leaves many vulnerable people in very precarious situations, the programme also left the viewer with a sense that charismatic, maverick people are bound to lead to trouble, and I found that deeply unsettling.

In the last World Cup, Holland played Costa Rica in one of the semi-finals. The Dutch goalkeeper, Jasper Cillessen , had played a cracking match, but in the last minute of extra time, with a penalty shootout almost a certainty, then-Holland manager Louis van Gaal substituted Cillessen for Tim Krul, a keeper with a worse goalkeeping record. In the end, the match went to penalties, Krul pulled off a series of great saves, and Holland won the match. What could have so spectacularly backfired ended with van Gaal being celebrated as a tactic genius, a “master, maverick and madman“.

Batmanghelidjh emerged from the documentary as a much loved, deeply motivated, compassionate woman who had got out of her depth, Kids Company becoming too big and complex. What worked so well in a small organisation, her unconventional approach, her spontaneous, big-hearted, ability to be flexible and responsive enabled her to work in ways that larger, more cumbersome, bureaucratic organisations couldn’t , increasingly became seen as a problem.

In the programme, the approaches that had made Kids Company so successful, so loved, so impactful, came under the cold light of scrutiny, as they have in the press over recent weeks. When seen under that harsh light, yes there were some questionable activities, but not many – what emerged into view was a maverick way of working, in all its imperfections.

There has never been a time in history when it’s harder to be a maverick. The Cambridge Dictionary defines a maverick as:

“a person who thinks and acts in an independent way, often behaving differently from the expected or usual way”.

But as organisations become more and more risk averse, when social media means that the condemnation of perceived mistakes can be so punishing and instant, fewer and fewer people are willing to really put themselves out there.

I guess I’m a bit of a maverick too. At least, I work in ways which, when things are going well could be seen as maverick, but in the cold harsh light of critical exposure would be seen as a bit odd. I am involved not just in Transition, but also in a brewery and in other things. I take all of August off work and even put my laptop in a drawer. When I give talks they could veer off into stories about all kinds of random things. I don’t fly. I work for an organisation that has ‘Being’ meetings and which starts all its meetings by giving everyone space to talk about how they’re doing.

We self-published a book with ‘Not available on Amazon’ on the back. I write blogs about slugs, my favourite painters and other things in a similar vein. When everything is working, that’s all (I hope) part of my maverick charm. But when it all goes wrong, those are the things used to denigrate your character and your work. But that ought never be a reason to stop doing those things.

Yes, mavericks can be flawed, and no, you probably wouldn’t want to give them the full financial run of an organisation because that’s not their strength, and of course, as an organisation builds around them they need a good Board to support them, but mavericks can make amazing things happen, and in a world where politicians are usually ‘on message’ tow-ers of party lines, I think we need mavericks more than ever before.

For all her faults, Batmanghelidjh was a remarkable catalyst of remarkable acts of human kindness, and she brought out the good in many people. After the riots in London she came out with the most passionate and insightful observations into what had happened. She once said:

For all her faults, Batmanghelidjh was a remarkable catalyst of remarkable acts of human kindness, and she brought out the good in many people. After the riots in London she came out with the most passionate and insightful observations into what had happened. She once said:

“Anger is waiting for someone else to do something. I tend to just become lethal, decide that something needs to be done and do it”.

This is a time where people need to step up, to show leadership, to inspire others, to start projects that many people might imagine to be impossible, to not take no for an answer. Doing so requires the ability to touch people, to inspire them, and that requires mavericks. Sadly, since that incredible World Cup semi-final, Louis van Gaal seems to have lost his maverick status, opting instead to play deeply dull football in his new role as manager of Manchester United. United supporters around the world can only dream that his inner Maverick might once more surface, take risks, be bold, playful and feisty.

If the story of Kids Company teaches us anything, let that thing be that mavericks can do amazing things, and that we should treasure them, rather than leaving us believing we must airbrush out all the risk and the edge that goes with who they are and how they work. Long live the Maverick!

Read more»

17 Feb 2016

In a final interview before she left Transition Network to take on new challenges, I sat down with Sophy Banks to talk about burnout and balance, our current theme. I started out by asking her what, for her, is meant by the term. You can hear the interview in full as a downloadable podcast (here), or read the edited transcript (below):

“Burnout, I think, applies at every level of scale. There’s clearly a personal kind of burnout that I’ve been close to and know many people that have been to that place where they’ve been out of balance or they’ve been giving so much or working so hard over an extended period that actually their health is very severely compromised by it. At the end point, it always ends up affecting our health physically, but possibly mentally as well.

People are exhausted, where their immune systems are trashed and they’re in a very long process of recovery to come back to full health, if they ever do. The long-term consequences is part of the characteristic of burnout.

Is there an example of burnout in your own life that you would like to share, or that is instructive?

Yes. I’d like to talk about Transition Town Totnes where I think we did a really good job with issues around energy and burnout. I remember that second Core Group meeting, really in the early days. You and Naresh had been doing those launch events and open spaces. You had seeded groups, and some of the groups had come around spontaneously. You called that first meeting in February 2007. I remember talking with Hilary Prentice, we were the two Heart and Soul founders. It was probably her idea, but we decided at the next meeting we were going to do a check-in around energy levels.

This was our second meeting and I think it’s really interesting, when you look back at the minutes, there it is. We had a go-round about – what are you giving, what are you getting from being part of this project, and how sustainable are you for the next one, three or six months? There were six or seven of us each focalising a group that knew they were putting on lots of events, and everyone knew they could probably last six months but not longer. Everybody! We were all so excited and wanted to give so much.

I remember at that meeting we went through that thing – what are we going to do about this? This clearly isn’t sustainable in the long term. We said either we have to get paid support, or we have to really scale back what we’re doing. So we said let’s try the first option, and if we can’t we’ll have to consider the second. In a couple of months, you’d managed to find some funding to get a paid admin support person. So for me, that’s a really good story of a group doing a really good job. I think it’s interesting that a year later we set up the Mentoring Project to give one-to-one support for the personal aspects of “how are you doing”, and reflection. I know there have been people that have been tired in the Totnes project, but as a project it has had very little real burnout.

In this story, eventually, the corrective loop worked, and I’ve met many people and seen many groups where the corrective loop hasn’t worked and resulted in people with long-term health problems from burnout in Transition and in many, many other movements for positive change, and what a paradox that is. I’ve heard people on trainings say, who’ve been in the environmental movement for 30-40 years, that burnout is ‘the dirty secret of the environmental movement’. That people used to burn out in those organisations from a relentless work schedule and culture, and they would just disappear and nobody would even ask about them. They would just disappear from sight. And how upsetting that is that these very dedicated people would just sink and not be seen again, and be left on their own to deal with the consequences of that.

One of the things that’s central to both of those stories is the person, yourself and/or Hilary, the people who say “I think we need to look at this in a bit of a different way”, to be the person to point out the elephant in the corner. There will be people listening to this I’m sure who are in groups who recognise the same things that you’re talking about, the same symptoms you talked about. What advice would you give to people in that position? To be their burnout whistleblower, the person who names it. What advice would you give to them?

I’ve met many people that have tried to put a check-in at the start of a meeting, where people go – that’s too touchy feely, or – why do we need to do that, or – we don’t have time…

…I remember Sharon Astyk wrote a piece where she even felt that putting chairs in a circle somehow smacked of a cult…

That’s right. There are extraordinary levels of defence against very simple pieces of good human technology in our culture. That’s the landscape that we’re in. One of the things is to have the confidence to put ‘How do we work as a group?’ as an agenda item; that people feel confident in all kinds of other things in that that are about tasks, but actually to say – I want this group to spend 20 minutes reflecting on how we want to work as a group, and to start opening that up as a normal topic of conversation in a group.

One of the frames that I sometimes use is – do we want this to be a group that cares about people? And if so we need to know how each other is. How can I care about you if I just don’t know if you’re ok or not? I like that parallel, if you meet someone in the street, you wouldn’t just go “what are you doing, how are you getting on with it, where are you on your to do list?”

The first thing you’d say is “how are you?” You may or may not want the short version of that, but you know that’s how we greet each other because it puts us in a frame of caring. I think if we can root it in that frame of being a place where we’re all about caring in Transition: we care for the planet, we care for our communities, our work in Transition as an embodiment of that, and actually we need to bring that right into this group where we care about each other and we know and we understand the principle.

When we have connected, trusting relationships, that’s when we have a group that can do wonderful things. So there’s not a competition between the time we spend staying sustainable, welcoming new people, and getting on with the doing. They absolutely complement each other.

I do think there is just a frame. It’s like there’s a frame inside us that has this strange belief that spending time on our relationships is a waste of time. As soon as we shine a spotlight on it in Transition it shifts, we just have to draw attention to it in a way that doesn’t trigger too much of a defence. I think how you stand for that – this is what I see, this is my agenda item, this is what I want the group to pay attention to, you do that with a gentle confidence, not an aggressive “this group’s terrible” but to do it with kindness, bringing the qualities that you really want the group to have. It makes it easier for people to relax into that conversation if it’s a stretch for them.

As soon as we’re outside our organisational frame, in to reminding ourselves how we are with our friends, that it really helps us find that part of ourselves that finds it completely normal to check how we’re doing.

You used the word ‘technology’ quite a few times in terms of social technology or group technology. If we think of Transition as being a social technology, a set of tools, resources and things, what would that technology look like or what would need to be different about it so that it could be designed from the outset so that burnout wouldn’t happen. Is it possible that we could design a movement which in its very design, designed out burnout? What would it look like? Is this the first organisation to have asked that question? I’ve never encountered it anywhere else before.

I think the powerful question is, is in any organisation or movement, “what’s the shadow for us?” “What’s the thing that we create unconsciously that’s destructive or harmful, and how are we like the thing we’re trying to change?”

I think the powerful question is, is in any organisation or movement, “what’s the shadow for us?” “What’s the thing that we create unconsciously that’s destructive or harmful, and how are we like the thing we’re trying to change?”

One of my teachers once said to me “one way to enquire into that is to look at your aspirations as an organisation, what’s your mission, and imagine the opposite of that, and then ask the question, how are we doing that.” So if Transition is all about exclusion, where are we exclusive. It’s quite easy to see there are lots of people who don’t find a place in Transition. If we’re all about healing a culture of manic activity and burning out the planet, where are we creating burnout ourselves. So that, I think is a really powerful question for any group or any organisation to ask.

It’s really important what the leaders do, and if the leaders don’t have good practices where they model balance themselves, if people see the leaders constantly doing and doing and doing and they don’t take time out and don’t reflect deeply and don’t get support, their groups and their movement will be created in their image very strongly.

It’s difficult as a leader to imagine how much impact you have around that. I have experienced that – it’s hard for me to even think of myself as a leader because it’s not my self-image, but I see that I have had a lot of impact. I think at those moments when the symptoms are starting to show, the response of the leaders is really critical. If they pay attention to it and give it value, that’s ¾ of the system. But if they’re ignoring it, dismissing it, haven’t got time for it, actually it’s very difficult for people with much less power or rank in the group to challenge the culture. In some groups there are strong leaders, in others it’s much more shared, so that can be very different.

But there are things that we can build into how our groups work. Nick Osborne’s done lots of stuff on effective groups, and I have this really simple three aspects of group life, one of which is task, and the other is all the structures that we need, the agreements, the roles, the clarity about our purpose. If we don’t have those it’s exhausting because nobody is on the same page together.

The third, which is the group that tends to get marginalised the most is about relationships, about caring, about building trust, about deepening into…I think it’s really interesting to ask – what is Transition, why are we so strongly called to it? You find really, really deep motivations about our love for our children, our profound sense of responsibility for life on Earth, the core of who we are as human beings and our identity. It’s all woven into why we do Transition.

When we open space up to hear each other about that, all of those petty irritations about “I always make the tea” disappear in this sense of being with human beings that share a deep love of life and beauty and this incredible natural world that we all live on and hold. So that bit about relationships I think is important.

There are some great statistics that help with burnout, like groups that spent 25% of their time on process, on how they work; on the how rather than the what are the most successful groups in every aspect; the most productive groups as well as the most long lasting.

Another antidote to burnout is having this culture, that a lot of people hear me talking about, of appreciation and celebration. If we don’t constantly keep reinforcing for ourselves this sense that what we are doing makes a difference, that each person’s contribution is valued, that we’re grateful for the incredible things that we have in these times, that’s also a thing that gradually depletes people. I think it’s interesting to think that sometimes people come to groups just to be seen and valued. They will give a tremendous amount if they get that back.

Read more»

12 Feb 2016

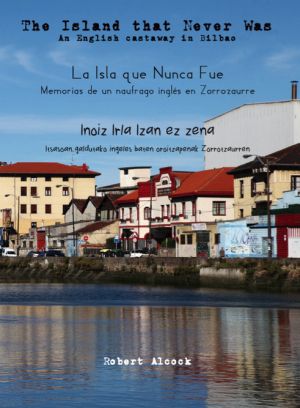

The spirit behind Transition, that invitation for a community to come together to reimagine and rebuild itself, takes many forms, not all of them choose to use the label Transition, and some, like the story told in this book, emerged before Transition but very much sees itself as being a Transition initiative in spirit. Earth builder, ecological designer, author, educator and occasional Transition Culture contributor Robert Alcock has just published a book that gives a powerful taste of one manifestation of that spirit, set in the city of Bilbao, Spain.

The book is written in three languages, English, Spanish and the language indigenous to the place where our story takes place, Basque. It tells the story of a forgotten barrio in the city, a small neighbourhood, “like a village in the city”, that had once been quite grand but which the city had largely forgotten about. It was a neighbourhood which he describes as “low-rent and bohemian, but despite appearances, not really dangerous.”

The neighbourhood was situated along the river, and had once been a vibrant dockland area. Now it still contained a few businesses, but also “the remnants of an industrial past that had never been tidied up”. Once it had been home to market gardens which made the most of the alluvial silt, but in the 1950s Franco decreed that Spain needed a huge expansion of industry, and the site became an Enterprise Zone. Factories arrived, canals were dug, and the area became known as Zorrozaurre. However, 30 years later, the economy collapsed, attention turned elsewhere, but 400 residents remained. By the year 2000, Bilbao was buzzing again, this time as a centre for design and fashion and culture, and developers started eyeing Zorrozaurre with interest.

It was into this somewhat down-at-heel setting that Robert and his partner arrived and set up home, initially getting involved in the creation of a ‘micro-garden’ on the waterside, which which gave people a sense of shared ownership of a common space for the first time.

It was into this somewhat down-at-heel setting that Robert and his partner arrived and set up home, initially getting involved in the creation of a ‘micro-garden’ on the waterside, which which gave people a sense of shared ownership of a common space for the first time.

As he puts it, “at least now we had something to squabble about”. The place also had its own social world, of parades, festivals, and a lively local graffiti art scene into which Robert immersed himself.

But at this point, the developers started to move in, appointing a superstar architect to “wave her magic wand and conjure up a sparkling Master Plan for the peninsula”. The rest of the book tells the story of how the community, in all its cantankerous, diverse, argumentative yet also really rather wonderful glory, responded to this. I won’t tell you any more as it’s a story you need to read and enjoy yourself. It’s a fascinating and heartening tale of the power we have but spend so much time convincing ourselves actually lies elsewhere, and asks the question “what if ‘meanwhile’ became a permanent condition?”.

It’s a quick read, beautifully illustrated, and can be order directly from Robert’s own website here.

Read more»

For me, my ‘being’ time takes the form of walks on Dartmoor (about once a fortnight, see right), riding my bicycle (most days, but just into town and back), working in my garden, listening to football on the radio (oddly meditative), listening to new music (might I recommend Max Richter’s recent piece ‘Sleep’ as some extremely fine ‘Being’ music), time just hanging out with family, the rare occasions I get to do any sketching, or rare trips away with Emma (my wife). I do also try to go swimming most lunchtimes, not something I always manage, but it is my conscious effort to try to keep in some kind of shape and to make the space for that.

For me, my ‘being’ time takes the form of walks on Dartmoor (about once a fortnight, see right), riding my bicycle (most days, but just into town and back), working in my garden, listening to football on the radio (oddly meditative), listening to new music (might I recommend Max Richter’s recent piece ‘Sleep’ as some extremely fine ‘Being’ music), time just hanging out with family, the rare occasions I get to do any sketching, or rare trips away with Emma (my wife). I do also try to go swimming most lunchtimes, not something I always manage, but it is my conscious effort to try to keep in some kind of shape and to make the space for that.