29 Jul 2009

Transport in Transition. A Guest Piece by Peter Lipman.

Transformation Moment: low carbon travel.

How, and how far, will we travel if we make the changes we need to in order to thrive in a carbon constrained society? For a range of interlocking reasons, the conclusion of this paper is that we will be happier, healthier and more resilient if we radically change from our current patterns to ones that fit into a relocalised world. In that world we will travel far less far and fast, overwhelmingly walking, cycling and using public transport.

How, and how far, will we travel if we make the changes we need to in order to thrive in a carbon constrained society? For a range of interlocking reasons, the conclusion of this paper is that we will be happier, healthier and more resilient if we radically change from our current patterns to ones that fit into a relocalised world. In that world we will travel far less far and fast, overwhelmingly walking, cycling and using public transport.

Background: why do we make the travel choices we do?

Underlying our choices about how to travel is why we choose to travel at all. Although some of us on occasion travel for its own sake, in fact the majority of the trips we make are to access something we need (schools, shops, workplaces, parks etc). A quick trawl of travel data from the National Travel Survey reveals that we are not going anywhere different from where we used to 50 years ago, but we are travelling further to get there. A case in point is the school journey; as the government extends our choice as to which school is attended, we end up with less choice on how to get there – the average school journey has increased from 2.9 to 3.3 miles in the last few years.

This means that if we want to move to a world in which sustainable modes of transport dominate, we have to ensure that the locations we all need to access in order to prosper and thrive are within reach by foot, bike or public transport. At the same time we have to think very hard about the kinds of physical infrastructure we create, as the environment we create impacts enormously on the choices we then (feel able to) make. And, of course, we need governments to have coherent, joined up policies that address people’s needs rather than just national budgets. A survey by Which? showed that, overwhelmingly, when it comes to health care people don’t want to travel a long way to get to a better hospital – they just want good provision nearby.

If, in addition to having a long way to go to reach our destination, we encounter a hostile environment when we step out of our front doors, we’ll tend to react defensively, often retreating into what seems to be a safe refuge of a car. On the other hand if we emerge into a space which welcomes people generally (not just travelling but also for example socialising and playing) then we’ll tend to react expansively, feeling able to walk or cycle. But of course it won’t help if that welcoming environment comes to an abrupt stop at the end of our street – so it needs to continue all the way to our destination.

What are the results of our current travel infrastructure and choices?

The climate change implications of our travel choices are clear. In the UK car use alone accounts for 13% of our total CO2 emissions and the forecast around the world is for transport emissions (even ignoring aviation) to continue increasing. This stands in very stark contrast to the emerging scientific view that targets for safe levels of greenhouse gases must be lower even than becoming carbon neutral – we actually need to lower existing concentrations of these gases from the atmosphere.

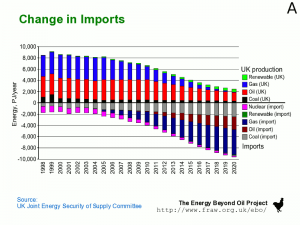

Climate change emissions resulting from actually moving people and goods come overwhelmingly from oil. As well as these, if we examine the entire manufacturing chain for transport, from building and maintaining roads, through to mining raw materials for making cars, and the running of factories and everything else along the supply chain, we find that coal is a another significant contributor to climate change emissions in the sector in addition to oil. And our dependence on oil for travel is another huge concern. The implications of this are explored further below in the “energy and money” section; in short we’re significantly far down the depletion curve for North Sea oil (with it having peaked in production a decade ago), meaning that we are going to have to import an ever increasing proportion of whatever we use.

Getting people out of cars and onto their feet, bikes or public transport doesn’t only reduce climate change emissions and our reliance on imported oil. Other additional benefits include increased health and also cleaner, safer streets, more freedom for young people to roam and communities less divided by roads.

Are there technological solutions?

Dramatically cutting emissions while still continuing to travel further and faster demands a technological fix. When the International Energy Agency (“Energy Technologies for a Sustainable Future: transport”) reviewed this subject, it concluded that such a fix would have to be one or a mix of:

“… there are only 3 basic approaches to achieving a transport system with very low emissions of greenhouse gases and low reliance on fossil fuels:

… a hydrogen fuel-cell system,

… a purely electric vehicle system, or

… relying on liquid fuels … derived from biomass”

Any system based on one or a mix of these measures would take time to implement, when the need for very significant reductions is urgent. In addition, technical solutions may create new, even worse problems. For example, demand for agrofuels as the substitute for oil based fuels plummeted as it became clear how they compete with food production. in 2006, the first year in which the US turned more of its corn into ethanol than it exported, tortilla prices in Mexico tripled, and food riots followed. Similarly, the switch to agrofuels led to a rush to establish palm plantations for purportedly “climate friendly” palm oil. The result was very significant rainforest destruction, and all that implies for biodiversity, and enormously increased (up to 15 times) overall climate change emissions from the clearing and burning of the forests.

Similarly visions of enormous fleets of “clean” electric or hydrogen or hydrogen fuel cell powered cars raise a range of questions, such as just how much extra energy will be needed to construct the necessary new infrastructure? A truly clean car would require all stages of its life to have been powered by renewable energy from the mining of raw materials, through its manufacture, shipping, sale and disposal, as well as for each and every electric charge used to power it. In an energy constrained world would we really choose to power cars over hospitals and homes?

All of these questions ignore another crucial issue – investment and purchase of all new technologies will inevitably include a front-load of fossil fuels. Do we know whether this could actually just be the final straw which pushes us over the edge of a climate tipping point?

Underpinning it all: energy and money

If we are to build new zero carbon transport infrastructures like that envisaged in the Centre for Alternative Technology’s Zero Carbon Britain then we need to be sure that we have sufficient energy and money to do so.

As North Sea oil and gas are rapidly depleted, the UK will move, in about a decade, from importing about 20% of our total energy to about 80%. How will we afford to pay for this? Interestingly, no other major industrial nation imports such a high proportion of its energy needs other than Japan. Japan of course is in a very different position to the UK; it has a healthy current account and balance of payments and a heavily export focussed economy earning, in theory, plenty of currency with which to buy energy.

As international fossil-fuel energy supplies become increasingly expensive and scarce and have to be sourced from either currently or potentially hostile geographic and political environments, how will the UK fund a rapidly growing deficit in its energy balance of payments? Until recently the Government argued that it did not matter that the UK economy has lost much of its manufacturing export base that once enabled it to pay its way, as our financial services sector would earn sufficient to balance the nation’s books. Recent developments in the financial services sector make that look like a particularly unrealistic and, frankly, dangerous position.

Energy literacy

Understanding national energy security issues and taking into account the total embodied energy in any system as well as its running costs is only a first step towards the energy literacy we need to acquire if we’re to make truly informed decisions about our future. We also need to become literate regarding energy returned on energy invested (“EROEI”).

EROEI is a simple equation. If it takes one barrel of oil in energy to produce 100 barrels (because all you need to do is drill a hole in the ground for the oil to gush out), then the EROEI is 100:1. Historically we’ve worked our way through easy to access or high grade supplies first, and, as you would expect, as we move to the less easy and lower grade supplies, the EROEI on fossil fuels is falling. For example, the EROI of oil and gas extraction in the U.S. has decreased from 100:1 in the 1930’s to 30:1 in the 1970’s to roughly 11:1 as of 2000.

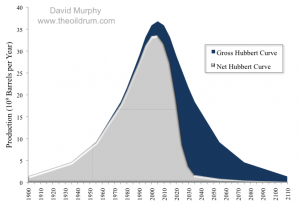

This has serious implications, well beyond just understanding that we’ll be using ever increasing amounts of the energy we produce to get more energy, trapping ourselves in a cycle of using more and more energy to produce an ever lower energy surplus. Applying this to the classic peak oil Hubbert curve yields interesting results:

“…The Hubbert curve represents the total gross quantity of energy available, and, as it is calculated, there are equal quantities of energy available on the left and right side of the peak. This, however, is only true in a gross sense. The net energy available (i.e. discretionary energy) is less. In other words, declining EROEI means that there will be much less net energy extracted post-peak than pre-peak on the Hubbert curve. … Due to declining EROI, by the time peak production is reached, 73% of the net energy available is already used …” (ref)

The energy and financial position we now face in the UK doesn’t just come down to an increasing energy balance of payments deficit at a time of declining EROEI and rapidly falling net energy availability, as these factors will both impact greatly on economic growth. In fact, an energy literate analysis of US economic growth found that that increases in energy productivity were responsible for 70% of economic growth. If this applies to the UK, then the circumstances we face mean no foreseeable end to our current recession; where then will we find the funding to completely transform our car fleets?

Relocalisation

Around the world, on average people make about 1000 trips (eg from home to work – that’s one trip) per person per year. Travel behaviour research from across Europe, the United States and Australia consistently shows that 10% of people’s car trips are shorter than 1km, 30% are shorter than 3km and 50% are shorter than 5km. This large number of small trips means that, even before relocalisation really starts to take hold, we have the potential to immediately intervene to support more cycling and walking trips – much more quickly than for any technological development and at a fraction of the cost. In fact, even under current conditions about half of the car trips we make could we switched immediately to sustainable modes (ref).

A transformation moment for transport

There are simple and transformational decisions which we could take. We could decide to invest in local sustainable transport and improve the physical infrastructure of our environments to make walking, cycling and local public transport the obvious, easy and safe choice.

If however, we are to consider technology based solutions, we need to learn to ask ourselves far harder questions than we’ve managed so far, including:

- what is the full energy cost of this transport intervention, including all of the embodied energy in the infrastructure needed as well as that from running the system?

- how long will it take to implement; could carbon reductions be achieved any faster with a different intervention?

- do we, as a society, have enough energy overall to carry through our decision?

- similarly, do we have enough money to carry out our decision?

Applying such an analysis might result in a transformed UK, in which we’ve maximised the use of our existing infrastructure and:

- nearly all urban trips are on foot, by bike or by bio-gas fuelled public transport

- rural trips which can’t be done on foot or by bike are mainly by community owned demand responsive vehicles, again bio-gas fuelled

- longer trips are mainly on an electrified rail network or by coach.

We don’t know whether humanity’s climate change emissions so far have caused a soluble problem or an insoluble predicament. We may already have pumped sufficient carbon into the atmosphere to have triggered feedback loops which will lead us well beyond a 2 degree temperature increase – and even a 2 degree increase could turn out to be far more dangerous than mainstream climate literature predicts.

Accordingly, applying the precautionary principle and minimising unquantified risks, we should be seeking urgently to move to zero carbon travel, which could happen fastest in a relocalised world. Does this mean forgoing the attempt to somehow find a technological fix through which we could continue travelling as far, and as fast, as we want? While that might seem hard to contemplate, we probably don’t have the choice – and in addition, we’d also address the fact that a result of current travel patterns is that we’re rapidly getting less healthy and less, rather than more, happy.

(Peter Lipman is Policy Director of Sustrans and Chair of Trustees, Transition Network)

Transport in Transition. A Guest Piece by Peter Lipman … « Culture Blog

29 Jul 12:24pm

[…] Read more: Transport in Transition. A Guest Piece by Peter Lipman … […]

Mike Grenville

29 Jul 12:46pm

While the amount of cycling is increasing there are many and varied reasons why the momentum to go by bike is not increasing faster.

The amount of cycling dosn’t happen by accident – if you compare the amount of cycling in Copenhagen, Amsterdam and Brussels the differences came about though government intervention.

One factor is fear by cyclists of car drivers. Here legislation could make a difference as there are many stories where drivers have not been prosecuted even when a cyclist has been killed. Where the onus is on the vehicle driver to take care of the cyclists such as Netherlands the level of perceived safety increases.

Taking a bike on public transport is possible in the UK but often not easy – (e.g. try changing trains at Clapham Junction; poor space provision on new trains; refusal of buses/coaches to take bikes etc).

If there was a wider choice and availability of good priced bike trailers than there is currently this would also help to make it possible for more journeys by bike.

Once one converts to using a bike rather than car, one starts to see the places around oneself in a different way. Anything within about 10 miles is possible to travel to casually and increases reliance on making more use of local services.

So it seems to me to increase more journeys by bike requires a mutli pronged approach both by legislators, organisations such as Sustrans and individuals.

Mari Cruz Garcia

1 Aug 12:21pm

A

Mari Cruz Garcia

1 Aug 12:29pm

“How, and how far, will we travel if we make the changes we need to in order to thrive in a carbon constrained society?”

It is estimated that 90% of average weekly travels are due to commuting to work. That is producing most of the Co2 emission. The Scottish Government published an excellent report about this fact and the impact of e-work (telework) on transport. I used the report try to promote a telework policy in my work. In the UK only 18% of the current workers are allowed to telework. Companies are holding cultural conceptions and schemes which are a legacy of the Industrial Revolution.In the Society of Knowledge, work should not be conceived as a “place” or a “timetable”, but an activity or a cognitive process. Yet, for that, we need a cultural change, we need to build a society based on mutual trust, in which managers do not to “watch” their employees, to check if they are working or not.

Jennifer Lauruol

19 Aug 4:17pm

I’ve just returned from a cycle trip from the English Channel to the Mediterranean, approx 1,200 km. It was lovely, if occasionally challenging.

Back in England, on a local bike trip, a bus driver drove straight across a mini-roundabout to cut me off and overtake me, because he didn’t want to wait until I had cycled 1/4 of the distance (a few metres) and entered the new lane in front of him.

We didn’t experience anything like this anywhere in France, where drivers are also held liable for cyclists’ safety.

We do need the legislation, and we need it quickly. We managed in the UK to put a ban on drink-driving; we’ve managed to get used to no smoking inside public places–both ‘unpopular’ pieces of legislation that have been accepted with little complaint. We need the government to make the change in the Highway Code.

Does anyone know a likely MP would would be willing to table such an Early Day Motion, to ‘get the ball rolling’?

Max Oakes

23 Aug 4:57pm

It is unfortunately too late to reply to this:

http://www.dft.gov.uk/pgr/roadsafety/roadsafetyconsultation/

But the govt have recognised that road safety is important and related to sustainability and social inclusion.

CTC (cyclists touring club- AA/RAC for cyclists) have a safety in numbers campaign. This recognises that more cycling tends to lead to fewer casualties-see Edinburgh/London etc .

The main problem UK cyclists face is that there are so few of them. Democracy can be bad for minorities.

The English cycling towns project is a good idea-focusing govt funds on towns like Durham and trying to build up the cycle traffic to a self-sustaining and self-protecting level in one place.

Big business prefers cars too, hence the attitude of much of the corporate media who hype cars and often ignore bikes. Big business tell the govt what to do. Cycles out sell cars in the UK, with 3m bikes imported annually (cars sales about 1.7 million). Exact figures hard to come by.

UK car sales are still collapsing (90% of car sales are on credit )and I am hoping for a follow on crunch when second hand cars start to become scarce/expencive/worn-out. I am hoping this will cut car use and make road cycling conditions easier.

I think encouraging recreational cycling on paths (and center parcs ) is worth supporting cos it allows people to learn to cycle. Confident riders are much more likely to have a go at commuting on real streets.

The revolution will not be motorised!

Mari Cruz Garcia

23 Aug 6:23pm

In addition to cycling, it would very positive if the UK Government could invest on a decent public transport infrastructure, like the one in Germany, France, Italy or Spain, among others European countries. When I lived in Germany, I could go everywhere in the countryside by combining train and bicycle. I try to travel by train here in the UK as much as I can, but it is always like a nightmare: train delays,journeys of 8-10 hours with no catering facilities, or you have to wait for an hour in the middle of nowhere because of an electrical failure. Sometimes, traveling by train for domestic journeys is twice as expensive as traveling by plane. Did the so called “liberalization” of transport and public utilities in the 80s bring a better service and choice for UK users?…Interesting question…

Sustran -sustran.org.uk- is doing an excellent work showing the correlation between social exclusion and the lack of a public transport infrastructure, which is forcing many working class families to choose between keeping their cars running or feeding their families healthily.

Helen

9 Sep 11:46pm

I’m not sure where this comment should go, but I just had a comment about travel… With COP 15 coming up soon, I know the usual will happen. All those climate campaigners who tell us not to fly anywhere will get on their plane and fly to campaign at the COP 15. Perhaps they could make a greater impact by NOT attending, en masse…and therefore avoiding the flight. Their absence might send a bigger message. Because there’s something that really annoys me, and that is the climate campaigners telling others not to fly, whilst they are jet-setting across the world to launch movies, make speeches, and participate in target-setting conferences that fail to meet their targets. I expect they’d fill a few planes loads each year… The thing for me that really rubs salt into the wound, is that there’s so many people in this world who will never have the opportunity to fly anyway as a result of their poverty (people in the UK included), and then the middle class campaigners tell them they shouldn’t fly, when they can’t even afford it anyway, yet the campaginers can…and they do, and their excuse is because they think they need to be there to make an impact. In this age of amazing technology, where people can be beamed across the world almost as if they are really there – possibly larger than life – why are campaigners still flying? I remember a newspaper article (probably the Guardian) a few years ago, which totalled the distances flown by directors and climate campaigners of environmental organisations. The flights were many and long. And it wasn’t only flights taken for work purposes: they were also flying abroad for their holidays with their families, for example to Europe where there are very excellent rail services. It seems inexcusable. How can they tell others not to do these things when they go ahead and do it themselves and, even worse, when the option to fly isn’t even available to many of those ‘others’? As they always say, action speaks louder than words. If those climate campaigners who go around the world making doom and gloom speeches were to make their doomsday scenarios by skype or video link, it would likely have a much greater impact. Rob is leading the way – he not only brings a message of hope (instead of doom), but I have also heard that he doesn’t fly. He is setting the very best example possible, and may others swiftly follow. I admit that at times I fly, but then I don’t go around telling everyone else that they shouldn’t.

Mari Cruz Garcia

10 Sep 10:29am

Helen,

Yours is an excellent comment and I couldn’t agree more. I also find a contradiction the message of many aristogreens and political figures (no names) when they go to work by bycicle and have an expensive car at home. Sometimes, the bycicles they have may be as expensive as a the second hand cars that working class people have to use, because there are no regular buses to go to their low paid jobs.

We can choose between cars and on foot, but many people cannot choose. They have to go long distances to find water, for instance.

There is no freedom when there is no choice.