Monthly archive for February 2016

Showing results 6 - 9 of 9 for the month of February, 2016.

9 Feb 2016

Last week I visited an amazing exhibition at the Wellcome Collection in London called The Secret Temple: Body, Mind and Meditation in Tantric Buddhism, (it’s on until February 28th). The exhibition is a celebration of the Lukhang, a temple close to Lhasa’s Potala Palace which was conceived by the fifth Dalai Lama and built by the sixth, a private meditation temple which showcased, in its extraordinary murals, ancient, esoteric and once secret practices central to tantric Tibetan Buddhism.

To step from the busy streets of the Euston Road into the quiet of the gallery felt, in itself, like stepping into a temple. The first thing you see is a beautiful film about the Lukhang. The story goes that during the construction of the Potala, the fifth Dalai Lama dreamt that the local spirits or nagas were upset by the amount of earth moving the construction necessitated, and so he promised to build a temple in a lake to pacify them. Here is the film that greets you when you first arrive:

In the end he died before work could start, the sixth Dalai Lama finally building it. The Lukhang was only reachable until recently by boat, and it features some of the most exquisite Tibetan art and wall painting. The current Dalai Lama, it is revealed at one point in the exhibition, never actually got to set foot inside the Lukhang, as he had to flee Tibet before he got the opportunity, but remembered as a child looking longingly at its roof from the windows of the Potala and wondering what it was like inside.

The exhibition uses the temple as the starting off place for an exploration of Tibetan Buddhist yogic and meditational practice, and the remarkable system they developed for creating physical and mental wellbeing. Beautiful statues, paintings, archive footage of lama dances in a monastery near Mount Everest filmed in the 1930s, along with commentaries from a Tibetan lama that adds insight and depth to what you’re seeing. One section takes you into the imagery of Tibetan tantra, of wrathful deities, flaming protector deities, and lots of skulls.

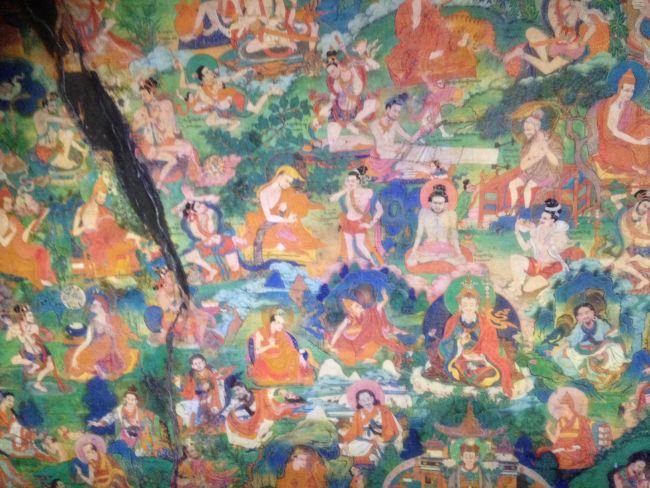

The centrepiece of the exhibition is three life-sized digital versions of murals from inside the Lukhang. Absolutely beautiful, lit from behind, in a darkened room, they capture an incredible civilisation and practices designed to develop and deepen compassion which were developed over many centuries.

While the exhibition itself was beautiful, fascinating and an absorbing immersion in an extraordinary, and much-endangered culture, the highlight for me came at the end. The final room featured a large screen showing a video which featured a couple of academics from leading universities both in the UK and in the US, the Tibetan lama whose commentaries had accompanied us through the exhibition, and the head teacher of a school in the UK which teaches mindfulness throughout its curriculum.

In the video, they discuss compassion, and the emerging body of science around it. They talk about how, in neuroscience, in the study of neuroplasticity, the practice of mindfulness and compassion has been shown to have huge benefits. One researcher talked about taking a random sample of people, teaching them a simple compassion practice which they then did for two weeks at which point they were then tested again, the results being that many benefits were discovered. Research now shows that being more compassionate results in us being happier, more attractive (“kindness” is the key quality people look for on dating sites), boosts our health and longevity, spreads to those around us, leads to more pro-environmental behaviour and leads to our feeling like we have more time in our lives. The head teacher talked about the amazing impacts she noted mindfulness practice having on kids at her school, on their school performance, confidence, and ability to be still and quiet.

At this point I was struck by the thought that here we had a culture that isolated itself from the rest of the world and spent over 1,000 years as a Silicon Valley research laboratory into the science of compassion, a Hadron Collider for mindfulness. Its whole culture was repurposed from being the region’s most feared warrior nations to being a nation of monks, nuns, temples, deep reflection and study.

I thought about how, in our current obsession with economic growth, so much is made of how important it is for businesses to be exporting (the UK seeks to double its exports by 2020), to be seeking markets elsewhere. While the UK, for example, exports some good things: culture; design; music; films; it also exports food that could just as easily have been consumed here, as well as torture equipment; tanks; missiles; bombs; money to off-shore tax havens.

I sometimes remark that Transition may turn out to have been the key export of Totnes when history looks back at these times. As I walked back out on to the Euston Road and headed for the Tube, I wondered how different a world we would have if we, like the Tibetans, measured our success in the world not by the amount of stuff we export, but rather by the qualities and the ideas that we export. By choosing to live more simply, more kindly, more compassionately, while such an approach would inevitably reduce our physical exports, we need to bear in mind that we would end up exporting something far more important, long-lasting and needed. A national Transition would be remarkable demonstration of compassionate action, and would also turn out to be our finest export.

Read more»

4 Feb 2016

The film ‘Demain’ (‘Tomorrow’) is proving to be one of the most remarkable catalysts for Transition and other bottom-up approaches that has ever been made. I recently saw it described by a friend of mine as “‘March of the Penguins’ for localists”. Mention of it often pops up in emails from people who have seen it. One recently said “Demain is working really well in France, it is a crazy phenomenon, never a documentary has touched so many people in France”. Another friend rang me from outside the screening he had just taken his son to in Paris, so thrilled by it he had to call me straight away to say how wonderful it was.

Demain in France

The film, created by Cyril Dion and Melanie Laurent, was premiered in Paris during COP21, and has since been seen by 560,000 people in France alone. It is now into the 6th week since its release, and this week has been the best week yet for the film, seeing a 29% increase in the number of people going to see it. This week it is on in 293 cinemas in France (see the list here). It is currently number 15 in the box office charts and has 103,000 followers on Facebook.

It has been nominated for a Cesar award (the French equivalent of the Oscars) for ‘Best Documentary’. Cyril and Melanie have appeared on all manner of TV chat shows (such as the one below) and the level of media coverage has been amazing. Its inspiring message has really hit a chord with people. As Cyril told me, “we are receiving every day messages from people launching projects or using the movie to support current initiatives”.

A review in Le Monde said described the film as “a phenomenon of society”. It added:

“In a France darkened by crisis and terrorism, this documentary is a ‘breath of hope’ … (it) presents the spectators with people who are not in the light, but who create, invent, and are preparing for the future. It takes them out of the impasse”.

Another, in La Vie, wrote that “this was a rare thing: the audience actually spoke to each other, before and after the movie! Indeed, many of them were there for their second or third viewing of the film”.

Demain in Belgium

It launched in Belgium a couple of weeks ago, and most of the screenings have sold out, with 13,000 people seeing it in its first week. Screenings have proved a huge boost for Belgian Transition groups. The Belgian equivalent of the Radio Times, their TV listings magazine, dedicated 7 pages to it, half of those to stories of what Transition groups are doing in Belgium. The Belgian Hub, Réseau Transition, asked groups for their stories of the impact the film is having. Here is what some of them said. Elisabeth (Liz) Gruié wrote:

“I live in Liège and watching Demain crystallised my appetite to support the ‘green’ cause and more specifically to get involved into sustainable and local projects… I contacted the team at Liège en Transition to see where I could be involved. I bought two shares in Les Compagnons de la Terre and I am now part of their communication team. Finally I invested into a Cooperative Bank and will open an account there instead of going for the brick-and-mortar banks. I started to buy and use the local currency (‘Le Valeureux’) and as a future switch to renewable energies I am now looking into Enercop to replace my local provider. So many changes indeed!”

Catherine Etterbeek wrote, “What strikes me is rather the impact on the people around me, who are external to the Transition”. David from Etterbeek in Transition wrote, “overall I think it reinforced the image that I have with my relatives and acquaintances (who begin to consult me on some issues) and I think it will pay off in the long term!”

Carolina from Ixelles Transition wrote:

“We welcomed new members since the film’s release. We noticed such enthusiasm around us that we decided to organize an event around the ‘day after tomorrow. ” This is called “Tomorrow, I promise” and will take place at the end of the month. Difficult to assess the impact before that date, but we’re getting close to 100 participants on Facebook + some very positive feedback about the organization of this event. It’s been a while that we did not have noticed such enthusiasm. We therefore expect a coffee debate on five themes of the film and will explore new ways to offer people to engage effectively”.

Demain in Switzerland and beyond

It recently also launched in French-speaking Switzerland, where it is Number 2 at the box office, with 21,000 viewers so far and momentum growing all the time! So what next? Distribution rights are currently being negotiated for other countries. We will keep you posted on news. The announcement about the Cesar awards is made on February 26th. In the meantime, if you haven’t already seen it, here is the trailer.

Read more»

3 Feb 2016

Back in May last year, I read in the papers, they found Anne Leitrim dead in her flat in Bournemouth. Her body had been there six years. Tragic, I thought, inconceivable. Then I asked myself just how many neighbours I have who would come knocking on my door. And the answer was zero. A few weeks later I tried to greet a woman I half recognised heading towards me on my street. “I know you,” she replied. “You’re the guy on his mobile phone all the time.”

The next month, on the cricket pitch, I tried to smack the ball into a lake, missed it and severed my Achilles tendon. The big lesson is never exercise. But it was a fantastic chance to read (which I didn’t take, I watched Breaking Bad). But I did start to walk, all over the ex-orchard turned into concrete that is Kiburn. Over the weeks, as I hobbled around the area on crutches, I saw bunches of wild grapes start to ripen, from green to purple to black.

One day, in the park, I got overtaken by an old Italian man. “Excuse me,” I said to him on impulse, “but do you know how to make wine?” He stopped, silver-haired, back ramrod straight. “The soles of my feet,” he replied, “are still red from making wine as a boy”. We were off. We were going turn Brent into the Napa Valley of the North.

The old man’s name is Paulo Santini. He is 84. He turns out to live 2 doors down. He last made wine 55 years ago in his village in Emilio Romagna. That summer he made it again, leading a crew that, over the months, has involved some 100 of us from the area. There was Nicola, a 70-year-old Italian former lorry driver with something of an eye for the ladies, Jane from Alabama, John Joe Moloney, a fruit-picking Irish engineer with his girlfriend, Vanessa, from Venezuela (think Sophia Loren on a retractable ladder in Willdesden), Rei’Anna and Roselyn overseeing quality control in Sunday finest; and two lynchpins of the Transition Town movement in our area, the two people who really made it happen, John Smith from three doors down, and George Latham.

Over summer weekends we picked the grapes as they ripened, knocking on doors and asking bewildered owners to let us in with our ladders. No-one said no. In total we picked 200kg (440lb) of wild vine Fragolino grapes. Then we trod them, out on my front stoop, plunging waist deep into the mash of grapes, our legs blood-red as we emerged from the barrel. We trampled barefoot, washing each other’s feet, because human skin can coax the peel off a grape better than any machine. My legs still itch from the tannin.

I used my daughters as human grape crushers. “This is more fun,” my eldest said, head barely visible, “than shopping at Zara.” “Do you have any scissors?” another woman who had travelled over from Bermondsey asked, then she cut off her black skinny jeans off at the thigh to join us in the barrel. I have still got the bottoms. “Vendemmia –” said Paolo, “this is the harvest.”

Unthinkable Drinkable Brent is the name of our project. Of course we were in it for the booze. We had a dream of 150 bottles. But it was about something else as well. Could we rediscover some lost skills? Could we reconnect with each other? Could we live on a street where none of us, me included, would die unnoticed? Where we would be more than someone passing on a mobile phone?

Some 200 bottles we made in the first year, and it is indeed borderline undrinkable; Brent Crude is its local appellation. The Archbishop of Canterbury has a bottle in Lambeth Palace, reserved, it is alleged, for unrepentant sinners. The bottles have all gone, before you come beating on our door, but next years crop (2015b – we had apparently got the year wrong the year before), looks like a bumper, with no less than 250 more bottles of unthinkable red on its way, and to wash it down, our new line, Transition Plum Slivovitz – harvested from the plum tree outside Kilburn Police Station…

Leo Johnson is one of the cofounders of Unthinkable Drinkable Brent and a member of the core team for Transition Kensal to Kilburn. He is the author of “Turnaround Challenge: business & the city of the future” and co-presents the radio four programme “Futureproofing”.

Read more»

1 Feb 2016

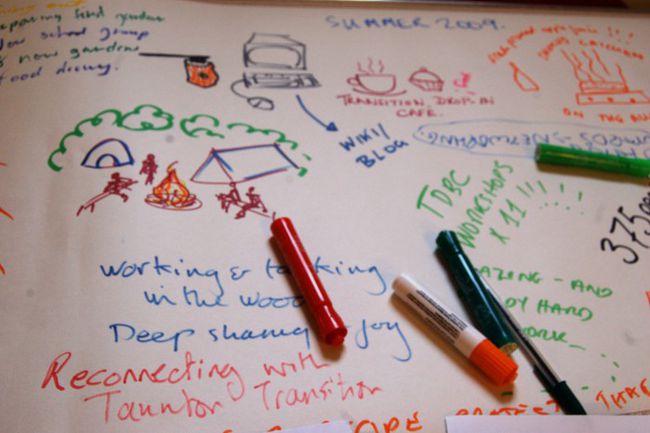

Chrissie Godfrey was formerly a co-ordinator of Transition Town Taunton (which she co-founded in 2008), but in 2012 suffered from a serious case of burnout. We asked her to tell her story, and we are deeply grateful for her honesty and for sharing her experience:

“When you first come together with other like minded people, when there’s a very pressing issue at hand and you’re learning more about it than you thought you’d ever learn, there’s a real energy around wanting to be a change-maker and wanting to make something happen. It’s a very exciting time when there’s a new group and there’s all sorts of possibilities out there. So even though the theme is burnout, this starts as actually quite a positive story.

The thing I want to say upfront is that any burnout was entirely of my own making. It wasn’t that Transition did this to me, it just so happened that at that time I was quite heavily involved in Transition, but there were other things going on in my life as well, including caring for a relative who was having a really tough time at the time as well.

I was thinking about what is it that creates the conditions for potential burnout to occur, and that maybe there’s something about personality types and particular skillsets that might end up being vulnerable to burnout, so this is a little thumbnail ‘why me’, because other people have avoided burn out.

People who are attracted to Transition are often those who can see opportunities. They can see Transition possibilities and they get very excited by those. They might be people who are accustomed to doing or to making things happen or to organising things. They might also be people who are quite good at networking, quite good at being unafraid of talking to people they don’t know or standing in front of a crowd of people and talking about stuff that they are passionate about.

There is a combination of people who can see opportunity and aren’t afraid to say “let’s have a go at this then”, plus being in other networks where people also have ideas. What it creates is a lot of things to say yes to. There’s a lot of us in Transition who love to say yes. You get an idea, it’s so exciting, you want to roll with it, and then there’s another idea and you can see how it links to idea number 1; then somebody puts their hand up and says “how about if we build in this bit” and it seems fantastic.

There’s a real sense of momentum that can build up quite early on in a group which is just brilliant. Relationships in the group are starting to flourish. In our group it felt sometimes like we were riding a crest of a wave. The Transition Network itself was quite new, and there was a huge amount of what I like to call the ‘energy of yes’.

What happened in our group with this sense of momentum was that a couple of us, again because of our particular work experience, got quite good at building ‘credibility’ with some local decision makers, movers and shakers. In our case that was definitely the local council. It was fun – it was fun being invited in to talk to the Chief Executive, and fun having one of the senior officers allocated to you to say – yes, let’s do some exciting work with every employee of Taunton Deane Borough Council.

We did loads of awareness raising workshops with everyone from the chief planning officer to the legal secretaries to the guy who drives the truck to pick up the dead leaves. It was absolutely brilliant. Because of that, we started to get quite a strong local profile. As a group, we would also turn up to stuff. We made sure we were quite visible.

Then, there’s something about wanting to be a magnet. You want to be a bit of a honeypot because you want loads of other people to come and join in and get involved. However, not all the things that you hope for actually happen. Whilst we had an amazing core group, which grew over time, ‘loads of people’ didn’t turn up to help. We had to learn to accept that there are so many different flavours of getting involved in Transition that may not mean actually joining your group.

I’ve started to think of it a bit like a family: you’ve got the family elders who are the ones who hold the centre. They hold the fort and are the decision makers, they’re the hosts for things. And then you’ve got the family members who want to be around you, who might like to turn up for a dinner party or Christmas and roll their sleeves up and do a bit of the washing up, but who disappear again back to their own lives.

Then you might have what I think of as the people down the street who just want to come once in a while for a cup of tea, just a casual drop by, no big commitment. Finally, you have your next door neighbours who don’t necessarily want to live in your house but they do want their house to be a bit like yours. These I think of as the other influencers in a town.

So we discovered that we had a core group of elders, who in our case held the centre, and then learned to work with the fact that the family members might want to turn up, but they won’t necessarily want the level of responsibility or time commitment that might come with being the elder…which was fine, except that by creating a lot of momentum, with a profile that’s visible, with more and more people are asking you to get involved in things, for me I reached a kind of tipping point. With my own internal push to sustain this momentum, I started to feel as though there was an entity that had got out of control.

As I say, there were other things going on in my life as well, but I look back on this time as a real tipping danger point. I wanted, in this interview, to flag up some of those dangers in case they resonate with anyone else.

One of these is that despite ourselves we can almost be drawn into the notion of a growth model, because we always want to do more. We want to be a bit bigger, we want to be a bit more visible, do another project. Because you’re part of a network and you’re always hearing stories about what people have done all over the world, which is obviously inspiring, there is a sense of it setting the bar quite high. Certainly for me on a personal level, I fell into a little bit of a trap of ‘unless I’m doing more it’s no good, it’t not enough’. Back to personality types – those people who say yes, often feel they ought to say yes more and yet again.

Then, there’s also something about the fact that even though it’s a voluntary group you can end up finding yourself in very professional contexts talking to other professionals and yet you’re sitting there without a job description (or pay!). So you have no boundaries over what you’re doing with this Transition gift time. You’ve got no external line manager saying “I think you’ve done enough now, that’s plenty now, you’re exceeding what you need to do”. Again, it’s a character thing, but that can really lead to self-exploitation if you’re not careful.

So there is a problem, if you’ve got people like me in the group who often say yes to things, you can end up with a group with unrealistic expectations of what it can handle. And being a voluntary group we didn’t do things that you would do if you were paid to work in an organisation such as proper project assessments, or clear role allocation, or sitting down and thinking about what the time commitments or skills would be needed. We’d just go “oh yeah, we’ll have a go at that”. And I do take a lot of responsibility for this.

It ended up that we said yes to things I really wish we hadn’t. The biggest one of these was the LEAF project (Local Energy Assessment Fund). This was a fund of money to help people in local communities get a better understanding of the energy needs of the households where they lived, and initiate projects around that. The problem was that applications were invited in just before Christmas, the decisions were to be made in January and then all of the grant money had to be spent by the end of March. And so all of the things I was saying about looking at a project and having the space and time to think through whether we can handle it, what the implications on our time might be, there was such a time pressure to go for this grant at all – and I did, and we got the money – that I nearly killed myself actually trying to deliver the project because I didn’t check out whether we had the people in the group willing to do the work.

Totally my own fault, but there was something about the system where there was this massive opportunity that I wanted to say yes to, but the time pressure was such that there wasn’t time for proper thinking back at grassroots level. I paid the price for that as it was absolutely knackering. Most of that project was delivered in the year where I finally collapsed and fell apart. It’s something for groups just to be mindful of, the tension between the speed at which the world works, particularly the world of grant aid in this instance, and the speed at which a voluntary group can realistically just have time to think and check out and test how much ‘energy of yes’ there is going on.

The other thing I have to ‘fess up to is that finding myself being a change maker is a bit of an ego ride – that happened for me, I’m not a saint. There’s something seductive about potential and wanting to say yes and wanting to be able to make change that matters to you. I came a cropper because of it, but I’m sure I’m not the only one out there in the Transition world who might resonate with that sense of – it is seductive to be able to do this, I want to make the change happen.

And I have a question: what do we mean by leadership in a Transition context? It’s almost like leadership’s a bit of a dirty word because we’re trying to be equitable and collaborative. Yet different leaders – if that’s even the right word – facilitators, motivators, whatever, will pop up from the mix in different places and leadership can sometimes just happen without it being thought through or talked about. What does that mean if I’m going to take a lead on this? What kind of leadership do we want for this particular piece of work?

Because we never talked about it, I think again because of my character and personality I probably took on aspects of leadership in the group which in the end became expectations of the group of me that I then found very hard to break. So it got into a little ‘Chrissie will’, because Chrissie always has, rather than stopping and going – hang on a minute, how did I get here?

There’s also another thing that contributed to my meltdown, which is that this kind of work can actually make you feel very vulnerable. Not everybody out there loves what you’re doing. I can remember when we were inviting people to train as home energy auditors and had quite a lot in the local press at the time about different things you can do to reduce your energy bills etc. I put my home phone number in the article because if people wanted to come to a particular public meeting I was going to be the point of contact.

I had a landlord ring up who screamed down the phone at me for about 10 minutes about how dare I be insisting on all this insulation because in his properties he tried to do that and all he had was damp running down the walls. He just went on and on and was literally screaming at me. The only thing I could do was in the end to scream back at him equally loudly so that he could hear there was another human being on the end of the phone trying not to burst into tears. I just had to talk me down and talk him down until he ended up apologising. And there was me, just an individual sitting in my sitting room at home. It really shook me.

Pack all of that up together with the fact that I was dealing with some quite difficult stuff in the rest of my life, I actually got very ill. I was helping deliver the Transition Conference 2012 which was an awful lot of work anyway, and was a brilliant conference. I’ll never forget that High Street we built as long as I live. But I came away from that conference absolutely and completely depleted to the extent that I was diagnosed as clinically depressed, which is quite a frightening place to be. It is hugely down to the fact that a personality like mine can end up taking on too much because of the energy of yes and the seductiveness of wanting to say yes. Actually seeing change happen that you’ve been part of making happen is so good, yet because we didn’t have overt conversations about leadership or managing our personal resources – in the way that we’re trying to manage the planet’s resources – the result for me was burnout.

Also we don’t have a clear way of how you step back from a position that you’ve had in a group. It’s almost like the models aren’t there yet for how you renegotiate your relationship. The only thing I could do was actually to put down everything. Stop absolutely everything. I was so unwell for about a year I found even working really hard.

The group is still going of course (mercifully no one is indispensable!) and I am proud to have been part of it”.

Read more»